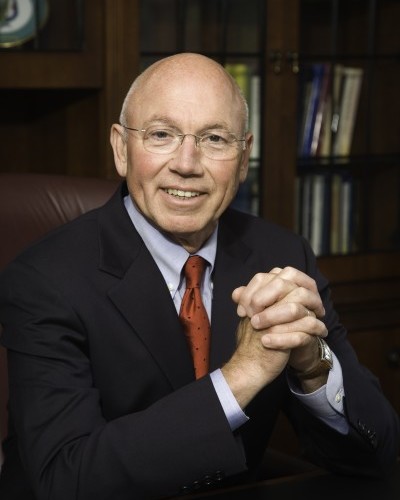

Education

Gene Tempel earned a Bachelor of Arts in English from St. Benedict College in 1970, a Master of Arts in English from Indiana University in 1974, and an Ed.D. from Indiana University in 1985.

Gene Tempel earned a Bachelor of Arts in English from St. Benedict College in 1970, a Master of Arts in English from Indiana University in 1974, and an Ed.D. from Indiana University in 1985.

Gene Tempel’s first experience with organized philanthropy came at the age of 26 as a school administrator at Three Rivers Community College in Missouri. Tempel’s early job responsibilities included working with local constituents to raise money for a new school building and he became increasingly fascinated with understanding the motivations of donors and volunteers.

“When I began working with those people on raising money,” said Tempel, “it really caused me to start thinking about why were people doing this — that is, raising the money? What motivated them to get together every Friday at noon and report to each other on how much they’ve gotten together? What was motivating the people on the other side to actually give the gifts?” His interest continued throughout his career, as he sought to deepen his knowledge of philanthropic motivation while serving in the positions described in the following sections.

Center on Philanthropy Origins

Perhaps the keystone of Tempel’s long career within the philanthropic sector was his role in establishing and leading the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University (now the IU Lilly Family School of Philanthropy). Three men were integral in launching this leading academic center: Hank Rosso, founder of The Fund Raising School®; Charles Johnson, former vice president of development for the Lilly Endowment; and Tempel, who was then vice president of external affairs for IU.

The idea for the center was prompted initially by Rosso’s desire for The Fund Raising School® to move into a university home upon his retirement. Tempel and Rosso discussed, “… the possibility that a university could not only house The Fund Raising School®, but could then begin formal study and do research around topics related to philanthropy, fundraising, the nonprofit sector, et cetera.” Tempel had always been passionate about how research could inform practice, and how practice could inform research. The idea for a new “center on philanthropy” at IU, with The Fund Raising School® as its cornerstone, fit this vision for connecting research, education, and practice.

“Broad education seems to be so important, and so I emphasize to people not just to get caught up in the technical skill — which is why I really like philanthropic studies so much, because people get to understand rationale, background, cultural differences, history. History makes so much difference in terms of understanding what you’re doing today. So I emphasize the importance of staying grounded in those things, and not just becoming a technician of sorts in management or fundraising or making grants or whatever. I emphasize those things, and staying grounded in ethical principles about what you do, asking yourself — checking yourself constantly on ethical principles and rationale — why you’re doing things, what motivates you, what your passions are, and working to your passions.”

Tempel engaged Johnson in conversations about the vision for a center. They brought on Robert Payton, a national leader in the emerging field of philanthropic studies, as a consultant. Working from Payton’s broad definition of philanthropy, including giving, volunteering, and nonprofit organizations, they developed an ambitious plan for a comprehensive academic center that would improve the understanding and the practice of philanthropy, both inside and outside the academy. The plan was supported by a $4.1 million, two-year initial grant from the Lilly Endowment in 1987.

From 1988 to 1993, Payton served as the center’s executive director; Tempel served as executive director from 1997 through 2008, which were years of major growth in the center’s activities. Under Tempel’s guidance, the center became a leading national force within the philanthropic sector, promoting education, research, and training. In 2012, the center transitioned into the nation’s first school of philanthropy, and Tempel returned to serve as the founding dean.

Other Contributions to the Field

Tempel remained committed to legitimizing the study and teaching of philanthropy throughout his career, and since 1998, has offered practical insight and wisdom as professor of philanthropic studies. Tempel served as the first elected president of the Nonprofit Academic Centers Council, an organization dedicated to the promotion and networking of centers that provides education and research on the nonprofit sector.

In addition to the academic study of philanthropy, Tempel was deeply interested in the ethics of philanthropy. From 2003 to 2005, he served as chair for the Association of Fundraising Professionals’ ethics committee. In 2007, as a member of Independent Sector’s Expert Advisory Panel, Tempel assisted in developing and publishing national guidelines for nonprofit governance and ethical behavior.

Part of Tempel’s strength as an educator in the field came from years of experience as a fundraiser. Tempel used those experiences to help create the Philanthropic Services unit at the center, which supported nonprofits in various areas of need through trainings and workshops. Tempel launched the first Women’s Philanthropy Council at IU. He served on the boards of countless organizations, including the Riley Children’s Foundation, Conner Prairie Museum, Sisters of St. Benedict, Learning to Give, Goodwill Industries Foundation of Central Indiana, Catholic Community Foundation board (founding member), and the Indiana Commission on Community Services and Volunteerism.

“Again, that’s one of the beautiful things about philanthropy. Philanthropy, you know, it goes over. It supersedes all kinds of other divisional aspects … It is something that covers the entire spectrum, so that it helps us supersede state lines, regional lines, whatever, to work on something that matters so much to all of us.”

From 2008 to 2012, Tempel served as the president of the IU Foundation. In 2010, he oversaw IU Bloomington’s $1.1 billion Matching the Promise campaign and Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis’ $1.25 billion IMPACT campaign. He completed an evaluation of the IU Foundation and built a strategic plan to help increase total voluntary support by $100 million annually. In 2012, he was awarded the Henry A. Rosso Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Fundraising.

Relationship to Philanthropic Activities in the State of Michigan

Over the course of his career, Tempel exemplified servant leadership in partnership with professional colleagues in Michigan and across the nation. The AIM Alliance was a novel collaborative effort between the university centers on philanthropy at Arizona State University, Indiana University, and Grand Valley State University in Michigan. AIM experimented with joint ventures in research, shared teaching of students, and collaborative professional training.

The IU Center’s board of governors included two members from Michigan: Dorothy Johnson (1998–2005, chairman 2001–2002) and Russell Mawby (2000–2006, advancement committee). The W.K. Kellogg Foundation partially funded the development of the Center on Philanthropy at IU and funded the launch of the Dorothy A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy in Michigan at GVSU. The philosophy of collaboration was infused in the founding of both organizations.

“… [Dottie Johnson and Russ Mawby] were effective in developing philanthropy in Michigan … by using their persuasive powers, by explaining and bringing people along rather than using any kind of coercive approach. That’s, from my perspective, the only way to do things. That’s the most effective way to do things and that’s what real leadership is all about.”

A common interest in educating pre-college students, led to a number of inter-related collaborations. These joint ventures involved philanthropic leaders in Indiana with funding from Lilly Endowment, and leaders in Michigan with funding from the Kellogg Foundation. The Learning to Give project in K-12 philanthropy education, led by the Council of Michigan Foundations, received substantial help and guidance from Tempel and the staff at IU. The Youth in Philanthropy Indiana (YIPI) project in communities throughout Indiana received assistance from philanthropy leaders in Michigan. A high level of trust and cooperation remained between the two states, nurtured by Tempel’s leadership.

Tempel was interviewed regarding his insights and experiences in working with Michigan’s philanthropic community and the Our State of Generosity (OSoG) partners. The following quotes specifically relate to the five organizing themes of the OSoG project.

Human, Financial, and Knowledge Resources

“That’s my deep belief in human beings — that all of us have a talent to do something. It’s just that sometimes we get in the wrong place and we’ve not been able to use our strengths in that position, and that’s what’s causing us not to be as good at what we’re doing as what we like.”

National & Global Implications

“In fact, many of us would argue that these infrastructure organizations help protect the kind of way in which our democracy works — where people vote with their interests and their dollars to help build a society that’s not possible to build through the ballot box alone. That’s an important and strong part of our society, and interestingly, a part of developing worlds that are growing constantly. People in China and India and Colombia and places all around the world are looking to strengthen their society by strengthening what they call the nongovernmental sector — by building philanthropy, by encouraging people to act on their own. That’s the richness of society that this infrastructure is helping to build and protect.”

Practical Wisdom

“… Approach problems with a sense of abundance rather than scarcity. That is, ‘how is this going to help the issue we’re trying to deal with, and how is it going to help us as an organization improve and grow as we partner with another organization,’ rather than entering the discussions with a fear that ‘we might lose something if we’re not careful, that somebody might take something away from us, that somebody might do something to compete with us.’ Those are the things I think that cause you not to take the big bold steps, and that’s, I think, the only way to approach this.”

“I think it’s important to be a good listener, to try to understand things from various perspectives.”