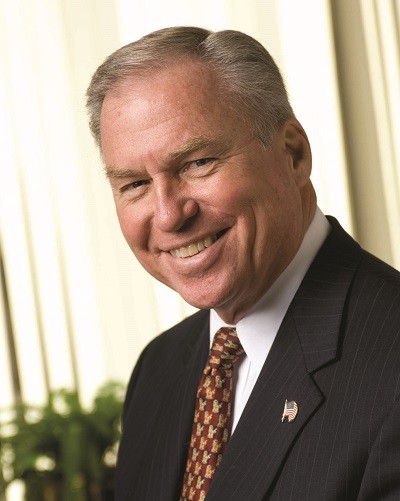

Hopkins worked at the Kalamazoo Community Foundation for 25 years, during which time the foundation played a leadership role in many statewide projects. This was due in part to the substantial assets of the foundation, serving a relatively small community, and the willingness of Hopkins and the board to take risks while supporting other foundations in their ideas and endeavors. During these 25 years, the foundation’s assets grew from approximately $38 million to $300 million, and in 2008, it was among the largest three community foundations in the country on a per capita basis.

One example of this aspect of his leadership was the introduction of the Foundation Information Management System (FIMS). The FIMS project aimed to create a single computerized system for Michigan’s community foundations. Despite the fact that the chief financial officer did not want to switch to FIMS, Hopkins saw value in working in partnership with the Council of Michigan Foundations (CMF), which had taken the lead on implementing FIMS at the rest of the major community foundations in Michigan. Hopkins felt that without the Kalamazoo Community Foundation’s backing, the project would fail, and so the foundation supported and adopted the system. FIMS, funded under the leadership of Joel J. Orosz, program director in charge of the Philanthropy and Volunteerism programming area at the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, was ultimately a success thanks to the hard work of many across the state.

As another example of his leadership, Hopkins brought the idea of the tax credit for community foundation gifts to CMF. He championed this idea to its successful conclusion, helping to negotiate the various challenges involved in passing major tax legislation.

“One, I’m not sure I ever had thought through how important the coming together and the support from the private foundation sector was, that we all stood together… But that was critical because those foundations were critical to the passage [of the 1969 tax credit]. They had a credibility that the community foundations did not have at that point in time in the history of our state. Secondly, I didn’t realize how long it would take. I thought I knew, but I didn’t realize we’d have to hire basically a lobbyist or a firm that would help us through the process, and how the waters changed daily in terms of who was supporting it, who wasn’t, what the questions were, and so on. The third was, all of a sudden, you’re in the public eye. That means that you could be criticized for your work and it takes just a ton of energy. The long-term benefits I think are worth it on so many levels, but you have to be prepared for it.”

Another project in which the Kalamazoo Community Foundation sacrificed its own interests for the betterment of the field was a rebranding effort among community foundations. To support this initiative, the Kalamazoo Foundation (which it had been called for 60 years) renamed itself the Kalamazoo Community Foundation.

Beyond his work at the Kalamazoo Community Foundation, Hopkins spent considerable time engaging with the state infrastructure organizations and acted as a board member and later vice-chair of CMF — a position he had left previously to become the chair of the leadership team at the national Council on Foundations at a time of considerable unrest among community foundations at the national level. Similarly, Hopkins served on the Midwest Community Foundation Ventures’ board before acting as its chair, and was a member of the community foundation committee for CMF.